It’s that time of year again – A-level and GCSE results days where social media buzzes with celebrations, proud parents, and university and college decisions. As someone who ended up at Harvard University from a low-income, single-parent household, and a non-fee paying school, I know how exciting results day can be.

But this blog post addresses the elephant in the room: beneath the shiny acceptance letters and toasts, there are glaring and persistent gaps in higher education. The data is sobering. While we should cheer the successes in higher education, we must also take a hard look at where improvements are still needed.

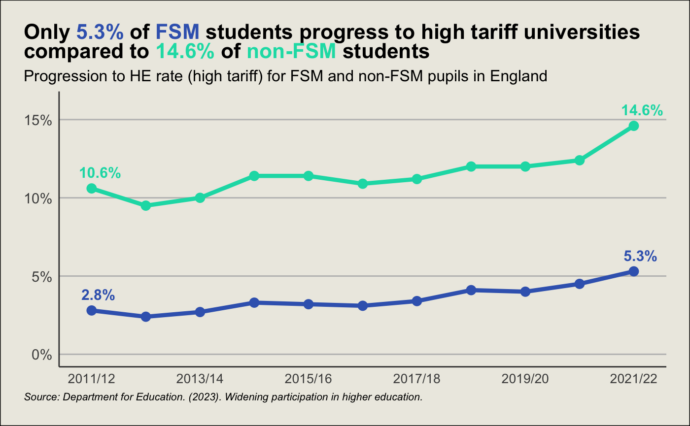

Free school meal students: progression to high tariff universities

TASO chart of Department for Education data

We begin with a harsh truth from the Department for Education: only 5.3% of free school meal (FSM) students enter high tariff universities (think Oxbridge or Russell Group), compared to 14.6% of non-FSM students. That’s nearly three times the high tariff progression rate for non-FSM students.

When reading this data, it’s more than just numbers – it’s a reflection of the barriers imposed upon students from low-income families. Such students are less likely to apply to certain types of universities and colleges even with the right qualifications. While I was one of the lucky ones, this graph highlights how few make it through. It begs the question: how many brilliant minds are we losing because of systemic inequities?

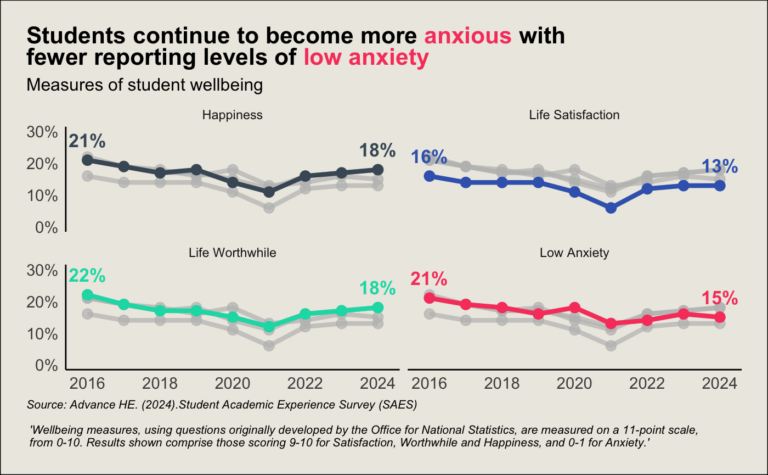

Student mental health difficulties

The Student Academic Experience Survey (SAES) – designed and developed by Advance HE and the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) – provides insight into student mental health. The survey has been examined in detail in analysis by TASO and the Policy Institute at King’s College London. The latest data suggests that anxiety levels are on the rise, while happiness, life satisfaction, and the sense of life being worthwhile are all showing little improvement.

TASO chart of SAES data

Such trends may not be surprising. Students face intense pressure as they juggle academic studies, finances, internship hunting, and often battle with imposter syndrome. The results highlight the importance of wellbeing support on campus.

This year, TASO commissioned three new projects to evaluate student mental health interventions, and TASO’s Student Mental Health Evidence Toolkit summarises the existing research into such interventions. After all, access to mental health services alone does not guarantee true inclusion or equitable support.

Among these pressures, imposter syndrome stands out. It’s an internal struggle that others cannot cure. Considering where I come from, compared to where I am now, I often battle with my own dose of imposter syndrome. But there is one thing to keep in mind: admission officers don’t make mistakes. We are here on merit and we are meant to be here.

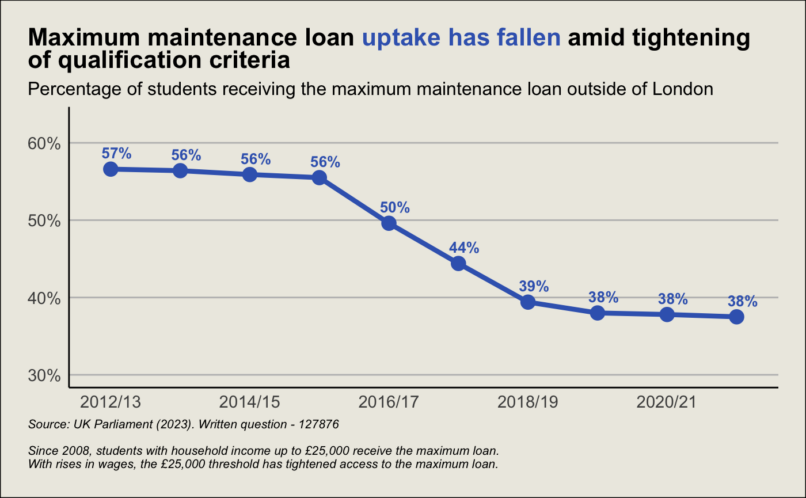

Static maintenance loan threshold

An issue that puts pressure on students – especially those from low-income backgrounds – is financial support, or rather, the lack thereof. The proportion of students outside of London who receive the maximum maintenance loan has been steadily decreasing. To qualify for the maximum loan, a student must come from a household income below £25,000 – a threshold that has been in place since 2008.

With no alteration of the threshold despite rising wages, fewer students have been able to access the maximum amount of money. In 2015/16, 56% of students outside of London received the maximum maintenance loan, in 2021/22, only 38% did.

TASO chart of student loan data

Why does this matter? For many students, financial support from parents is not an option, making the loan their sole source of income. And with rising living costs, the loan may not stretch as far as it used to. The tightening of access to these loans creates yet another hurdle for students fighting an uphill battle.

On the other hand, tightening the qualification criteria for the maximum loan may be seen as a necessary step. At one point, half of all students were receiving the maximum maintenance loan amount, raising questions about whether thresholds were set too low. Perhaps the government is filtering access to those who need it the most.

A disproportionate impact

Nonetheless, the reality remains that many students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, struggle to make ends meet. The intentions behind tightening the criteria may be reasonable, but it is likely that the consequences will disproportionately affect the students who can least afford to attend university. As a result, hardship funds have become increasingly important. In 2018/19, the total amount in hardship funds was £45.9 million, an amount that had almost tripled to £121 million in 2020/21.

These graphs are just a snapshot of the issues in higher education. So, while we celebrate the achievements of those who crossed the finish line on results day, it’s crucial to remind ourselves of those who start the race further back, and those who may not have been able to finish at all.