Last week, we published the latest edition of our now annual report on student mental health in the UK. The survey we used is conducted for Advance HE and the Higher Education Policy Institute. Fortunately, for the last few years they’ve been kind enough to share the data with us, enabling us to conduct this analysis.

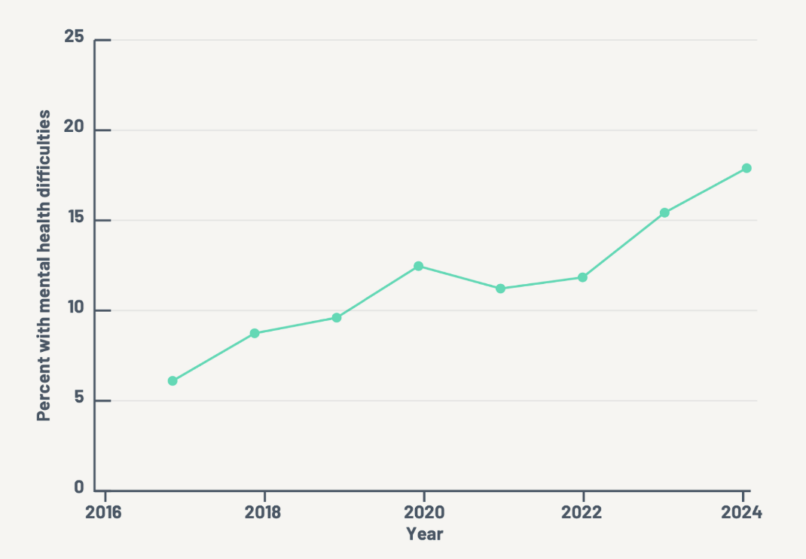

Running the same analysis each year has started to feel like waiting for the cliffhanger at the end of a TV season. We anticipate the new data, then watch as my statistical software spits out the latest results. . Each year, we hope for some positive news–for the graph showing the rise of student mental health difficulties to reverse, or at least flatline, to give me the sense that things have stopped getting worse.

Once again this year, I have been disappointed. The rise of mental health difficulties among students has continued unabated, and while the increase was smaller this year than in previous years, the overall rate has tripled since data was first collected in 2017.

This rise is secular – it affects everyone – but it is not evenly distributed. As we highlight in the report, LGBTQ+ students are the most affected–both by mental health difficulties themselves, and by the rise in these difficulties. Trans students are 150% more likely to experience these difficulties than cis students, while lesbian and bisexual students face almost four times the risk compared to their straight peers.

The note of optimism I was able to strike last year – that the gaps between these groups were shrinking -–has faded this year, with gaps between cis and heterosexual students and LGBTQ+ students widening across almost every category.

These are particularly poignant findings in the context of this being LGBTQ+ history month, at a time when some believe efforts to support and include people–regardless of how they identify and who they do or don’t love–have gone far enough. These results show that we haven’t gone nearly far enough. As universities seek to address the enormous challenge that rising mental health difficulties pose to their students, they must also carefully consider who is most likely to be suffering, and how support can be tailored to meet their needs.

Michael Sanders is Professor of Public Policy at King’s College London and TASO’s academic lead. He is also the chair of trustees of the Nightline Association. Julia Ellingwood is a Research Fellow at the Policy Institute at King’s College London.