Effective transition support is crucial in enabling students to integrate and to develop a sense of belonging.

Disabled students continue to face challenges during their journey into, through and beyond higher education, despite the positive changes in supportive legislation, funding and enhanced provision.

While disabled students may have already developed an extensive set of organisation, self-management and resilience skills, they may have more difficult study trajectories, experience less satisfaction with their experience and worse education and employment outcomes in comparison to other students.

To strengthen the support that higher education providers (HEPs) give to disabled students during their transition into higher education, TASO commissioned RSM UK to work with three HEPs to develop a blueprint for transition support. The blueprint provides a set of evidence-informed activities and programmes to enhance disabled students’ transition.

Supporting disabled students: A blueprint for multi-intervention transition support

This blueprint offers an overview of a series of activities: seven targeted at disabled students, and one at staff. We recommend that providers use this blueprint to start to plan their work, in conjunction with the accompanying guidance. For a more detailed overview of the blueprint, see the Enhanced Theory of Change for multi-intervention transition support.

Theories of change and reports: examples from universities and colleges

The providers we worked with also developed Enhanced Theories of Change, which will support the sector to better understand and evaluate their interventions. The providers’ reports and Enhanced Theories of Change are below. If you would like any of the content in a different format, please contact us.

- The University of Bath: Supporting transition to Bath for students for lived experience of Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC)

- The University of Birmingham: Supporting conversations about Reasonable Adjustments in Personal Academic Tutorials

- City College Norwich: A package of activities to support the transition into higher education for disabled students in college-based higher education

A tailored approach to selecting transition-support activities

The goal is to enable HEPs to employ a tailored approach to selecting a suitable activity, or combination of activities, to support their students. The activities should be developed using a co-creation approach that involves collaborating with key stakeholders (students, staff, and allied professionals) in designing and implementing transition-support activities. The blueprint focuses on early transition into higher educatin, but its insights might be relevant for other kinds of course transition.

Implementing the blueprint will enable HEPs to create inclusive learning environments and practices. It will help staff support disabled students’ transition into higher education. Disabled students can benefit, in particular, through:

- improved satisfaction with the HE experience

- increased retention and completion in HE, as well as more successful progression into further education and/or employment. and completion of HE

- improved self-determination, wellbeing and confidence to succeed in HE.

The blueprint section provides guidance and recommendations on how to use the resources in order for HEPs to strengthen their transition support.

Blueprint diagram

Blueprint diagram – Supporting disabled students: A blueprint for multi-intervention transition support

The blueprint provides a set of evidence-informed activities and programmes to enhance disabled students’ transition into higher education.

- Scroll through the blueprint for multi-intervention support, embedded below

- View a full-size version of the blueprint here (Mural)

- View a PDF version of the blueprint here (PDF)

Enhanced Theory of Change for multi-intervention transition support

The Enhanced Theory of Change for multi-intervention transition support is a detailed chart showing inputs, activities, outputs and short-term, intermediate and long-term outcomes. (The blueprint above is a streamlined version, based on this more detailed theory of change).

- View a full-size version of the Enhanced Theory of Change in Mural here (Mural)

- View a PDF version of the Enhanced Theory of Change here (PDF)

How to use the blueprint

How to use the blueprint

How to use the blueprint

Find out more about how to develop your transition support for disabled students.

For the purposes of this blueprint, we have defined the transition period as including the students’ first term while they settle into their higher education provider (HEP) environment and begin their course.

Although you may wish to implement standalone, single activities/interventions (for example, welcome events), we recommend applying a more holistic, multi-intervention approach by embedding transitions support across all aspects of student and staff academic life.

Transition support should be included in staff induction activities, and, over time, activities should be embedded in the transition process for all students entering HE. This should include targeted outreach and support to specific groups (for example, by condition or broad grouping, such as neurodivergent students) as needed.

We recommend that you use the stepped approach outlined below to develop your disabled students’ transition support.

Step 1: Identify

Conduct an audit of disability-related services, support and initiatives that are currently available at your HEP.

- Use data already available within the institution to identify any inequalities in outcomes. Data might include a combination of institutional data and the results of programme or project evaluations with disabled students.

- This step may also involve collecting new data through surveys or panels with students to better understand both current support provided and gaps in provision.

Step 2: Clarify

- Use the blueprint to map support currently available and to identify the gaps in existing support, systems and processes. Go through the same process to highlight both:

- Gaps in outcomes. For example, you may find that disabled students have multiple opportunities to engage with current students, but parents and supporters have no opportunity to find out about the support available to disabled students and;

- Inequalities in outcomes. For example, your internal data might tell you that disabled students are at greater risk of dropping out in the first term than their non-disabled peers. Further investigation might reveal that disabled students have little or no opportunity to experience life on campus prior to attending the HEP which could affect students’ sense of belonging, leading to students being at a higher risk of dropping out.

- Based on findings, clarify which areas – where gaps in support and inequalities in outcomes have been identified – offer the most scope to be changed and the potential to have the most impact. Consider the input needed to be able to deliver the activities. Your focus may be at any point in the student transition journey from pre-offer to post-entry.

Step 3: Using the blueprint to develop a theory of change

- Having identified the areas to address, use the blueprint to plan the desired changes to the implementation of your transition support.

- The assumptions that underpin each of the activities are key to this step. It is important that the assumptions can be fulfilled to increase the likelihood of your programme being successful and to optimise their delivery. We suggest that you closely examine these assumptions when building your programme of support. All assumptions associated with a specific activity are indicated by the blue boxes in the blueprint. The blue boxes in the blueprint link to the set of assumptions linked to the activity.

- At this stage it is important to start to develop your theory of change. See TASO’s theory-of-change guidance here. Developing the theory of change will allow you to map how activities/sub-interventions lead to short, intermediate and long-term outcomes, ultimately illustrating how your transition support is theorised to achieve your final impact. The blueprint will help you identify and develop relevant outcomes. You may also find TASO’s post-entry Mapping Outcomes and Activities Tool (MOAT) and the three HEP Enhanced Theories of Change developed as part of this project helpful:

- Post-entry Mapping Outcomes and Activities Tool (MOAT)

- The University of Bath: Supporting transition to Bath for students for lived experience of Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC) (PDF)

- The University of Birmingham: Supporting conversations about Reasonable Adjustments in Personal Academic Tutorials (PDF)

- City College Norwich: A package of activities to support the transition into higher education for disabled students in college-based higher education (PDF)

- Developing a robust theory of change requires identifying key change mechanisms. Changes mechanisms are linked to outcomes and are indicated by the circle containing the letters CM followed by a number in the blueprint. The change mechanisms explain how the activity/programme is expected to lead to the anticipated outcomes and impacts.

Change mechanisms are explicit and describe the underlying processes that drive change. Think of them as the active ingredients that are needed to improve the likelihood of the outcomes.

Change mechanisms can be conceptual or operational, and they can be classified into various types, such as behavioural, cognitive, social, organisational and policy mechanisms. Change mechanisms can be evidence-based – for example, evidence from other contexts suggests that early engagement with disabled students helps to develop a sense of belonging in HE.

Change mechanism example

If one of your desired outcomes is to ‘Increase HEPs’ positive engagement with current students’, this is linked change mechanism, CM1 (See the change mechanisms listed in the Enhanced Theory of Change here):

Early engagement with HEPs ➛ students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey ➛ improved knowledge and/or increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services.

The change mechanism, or active ingredient (‘students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey’) leads to the short-term outcome that they are more likely to have increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services. The intermediate outcome is that a trusting relationship means that students are more likely to share information about their disability with staff, which means that they are more likely to receive the support required. This in turn leads to the longer term outcome that disabled students are more satisfied with HE, with improved wellbeing and self-determination.

Step 4: Build

- Having identified the outcomes and change mechanisms in your theory of change, the next step is to determine how best to deliver transition support to achieve the desired outcome.

- Use the blueprint to track from outcomes to the activities that will support you to achieve your outcomes. Build these into your theory of change.

- Revisit the assumptions underpinning the activities, and make sure these are built into your theory of change. It may be that your outcomes need to be amended to take account of the assumptions.

- Design your new programme of activities by dovetailing them with what is already being implemented at the HEP. To ensure that you are adopting an evidence-informed approach to transition support, when introducing new activities to your suite of support it is important that both the new activities and those that you currently deliver are informed by evidence. This may mean that you need to amend existing activities or stop delivering particular activities.

- It may be useful to involve other stakeholders with the relevant knowledge and expertise to help deliver the activities.

- Keep your own institution and context in mind when considering what might work for disabled students and what you are able to offer bearing in mind existing capacity and resources.

Step 5: Implement and evaluate

- It is important to monitor and evaluate your programme of activities, to establish: what works well; what aspects might need improvement; and whether your theory of change needs to be amended. All of which helps to build the evidence base for what works to support disabled students’ transition into higher education.

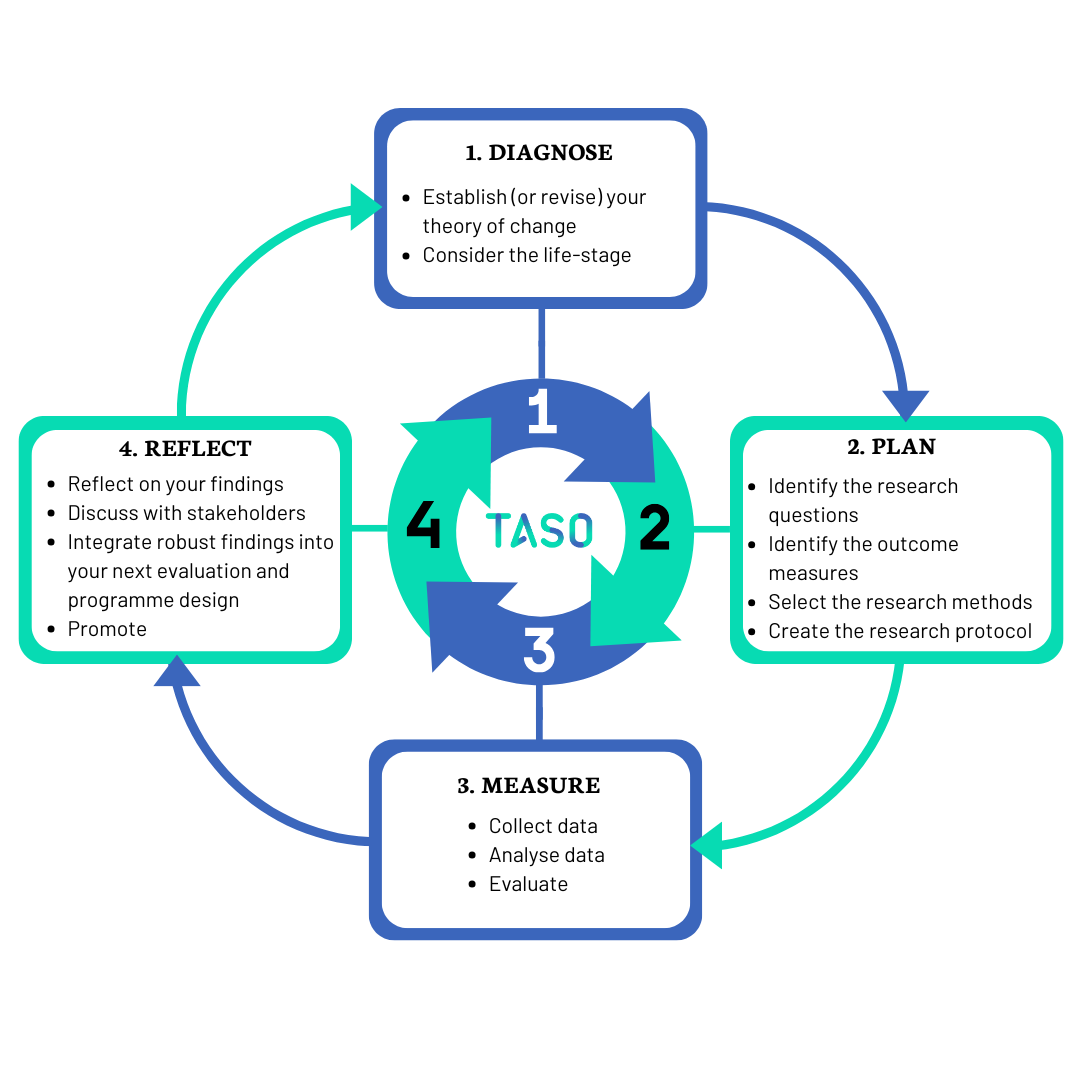

- We recommend using Steps 2, 3 and 4 of TASO’s Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (MEF) to develop your evaluation work.

- MEF Step 2 is Plan. You will need to use your Theory of Change to develop the questions that your evaluation will seek to answer. These overarching questions will determine the scope and approach of your evaluation.

- MEF Step 3 is Measure. This will help you plan your data collection and analysis.

- MEF Step 4 is Reflect. It is crucial and findings from evaluations are shared to enable learning

TASO’s Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (MEF)

Inputs: resources required

Inputs: resources required, such as data and time

We have identified five types of important input: information and resources, individual and institutional time, institutional inputs and data. However, the last, data, is foundational to all other inputs.

1.1 Information and resources

This includes all the resources (including financial, time and personnel) required to deliver the interventions/programmes and underpins and facilitates all other inputs included below. It also includes access and participation plan (APP) spend on student success and/or disabled student funding available at the HEP, the development of all printed and online information/materials required for delivering the selected activities. The materials should be informed by evidence; therefore it is critical for them to be developed by engaging with lived experience experts and using the contextual information and data collected as part of 1.4 below.

1.2 Senior leadership buy-in and support

Buy-in from senior HE leadership is critical to any intervention’s success. Such support is crucial for prioritising the transition of disabled students as part of an HEP’s mission and strategic action plans, allocating appropriate resources and time towards interventions and programme. Moreover, senior leadership commitment can be an important factor driving the engagement of staff delivering transitions support.

1.3 Individual and institutional time

HEP staff who support disabled students with their transition (including the Disability Service team, academic staff, and student support services) require time to facilitate the implementation and evaluation of the intervention / programme. The time of external advisors (such as inclusivity and disability practitioners) is considered essential for providing expertise, leading training and mentoring programmes, and giving feedback on existing materials/processes. Additionally, disabled students’ time is an important input that allows them to engage with interventions / programmes such as buddy schemes, peer-to-peer mentoring, and open events. Finally, time and engagement by other stakeholders such as parents and supporters can allow them to engage with specific interventions / programmes designed to draw upon their support and encouragement

1.4 Institution systems and processes

This might include tangible inputs and systems such as infrastructure (for example., IT/software), as well as non-tangible inputs such as processes and policies within the HEP (both existing and needed to be developed, if applicable). Systems and processes also link to wider inputs external to the HEP, such as national/local funding and support programmes aiming to provide financial support to disabled students to help with any essential costs arising because of a disability.

1.5 Data

HEPs should establish data collection practices. The types of data that are important to collect to fully inform intervention and programme delivery, identify gaps, and improve provision include: number of students engaging with each activity, number of activities led, and materials produced, and the types of students involved (e.g., based on disability types or other equality characteristics of disabled students). HEPs are encouraged to use data already held within the institution to identify any gaps in provision. Collecting data on outcomes is also important. The first step should include identifying sources where HEPs may already be collecting outcomes data as part of broader monitoring and evaluation activities.

Following this, HEPs could consider sources such as: external secondary data (such as HEP-level data published by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), and primary data collected via, e.g., student surveys. Priority should be given to measuring short- and medium-term outcomes over longer-term, and behavioural outcomes over non-behavioural outcomes. Where the latter are measured, validated scales should be used. For additional guidance and examples of the data that can be collected, a post-entry typology of student success activities has been developed by TASO can be accessed here.

Intervention 1: Multi-day support programme

Intervention 1: Multi-day support programme

Multi-day support programmes, which might include academic skills building, time management, wellbeing stress and anxiety workshops, broad information about reasonable adjustments, sessions on how to cope with coursework, and activities that enable students to familiarise themselves with the HEP campus. This is also an opportunity for HEPs to provide sessions on how to use the assistive and accessible technology (ATech) provided by the HEP (e.g. built in accessibility features in the virtual learning environment and specialist software on campus computers).

Timing

Offer-holder and post-entry transition stages

Activities

This programme can be delivered in the form of a multi-day (normally 3-day) summer or spring school for offer holders depending on their admission date.

It can also be delivered in the form of a series of individual workshops during the induction week for students who have either been accepted later in the admissions cycle or who are unable to travel to campus in advance of the academic year, or who have come through clearing.

Change mechanism

Early engagement with HEPs → students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey →improved knowledge and / or increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.3 We assume that the activities generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 2: Welcome events

Intervention 2: Welcome events

Personalised welcome events might be better suited to neurodiverse students, students who have complex needs, or students with higher levels of uncertainty and anxiety. HEPs should consider, for example, offering 1:1 tours to disabled students to enable them to visit the campus in a calm, quiet way as HEP-wide open days or inductions can be busy and overwhelming. This could include meeting with a student support officer, the disability support team, and individual academic departments.

Ideally, such tours should be conducted by a lived experience ambassador. Events should also provide students with information that can increase awareness of their journey throughout their time in HE to support their decision-making (such as, whether or not the HEP provides relaxed graduation / opting out of ceremonies as an option or information about support for transition into further study or employment). They can be tailored to specific disability groups or as general events, with clear signposting to manage student expectations. Alternative sessions should be organised for students that miss personalised welcome events due to the late disclosure of their disability. [Type 1 evidence]

Change mechanism

Early engagement with HEPs ➝ students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey ➝ improved knowledge and / or increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.3 We assume that the interventions / programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 3: Tailored workshops

Intervention 3: Tailored workshops

This includes organising, recruiting for, and hosting live workshops that provide students with access to support services within the HEP and simplifying any relevant onboarding information, such as how to access course materials, navigate the campus and contact the relevant staff to access information or discuss their specific needs.

Timing

Offer-holder and post-entry transition stages

Activities

Activities can be delivered either in-person to enable students to learn together and actively engage with both the workshop content, as well as institutional staff and other students. This has been associated with an increase in disabled students’ confidence to succeed in HE (Harley, 2023). [Type 2 evidence]

Workshops can also be delivered via telephone or online in order to increase awareness of and engagement with onboarding information, support services, and course content with the aim of reducing accessibility barriers for disabled students. [Type 1 evidence]

Ideally, both formats should be delivered as providing participation options over an extended period of time. and in a range of formats, can maximise effective implementation. The HEP should further raise awareness of the workshops via relevant networks, forums, and newsletters.

Change mechanisms

- Early engagement with HEPs students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey improved knowledge and / or increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services

- Familiarisation with and early awareness of student life → students are better prepared for HE → improved experience of HE

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.3 We assume that the interventions / programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 4: Needs assessment

Intervention 4: Needs assessment

Planning for the transition process begins as early as possible is important to the success of transitions support. It is also important that both pre- and post-entry needs assessments are conducted to identify key transition requirements so that they can be addressed with reasonable adjustments and other tailored activities / programmes.

To clarify, needs assessments can be wider than an assessment specifically conducted for receiving a Disabled Students’ Allowance (which all HEPs may not be validated to conduct). To do this, it is advisable that key stakeholders are involved in the process, including disabled students themselves (for example, by declaring their disability), parents/supporters (for example., by supporting the transition), and HEP administrative and academic staff (for example, the Disability Service team).

Timing

Pre-offer, offer-holder, or post-entry transition stages

Activities

- Parent / supporter-educator consultations at local schools to provide parents and supporters with information about the support available at HE as well as the life skills students need to develop during their first term. Type 3 research has shown that parents and supporters of disabled students prefer to be more involved in the transition planning process (Ruble, McGrew, Toland, Dalrymple, Adams and Snell-Rood, 2018). Parents and supporters are lifelong advocates for many students with disabilities and sharing that information with them can help maximise students’ readiness and competencies across the different life skills that are required when entering HE. [Type 3 evidence]

- Direct referrals to the Disability Service team for tailored Disability Action Plans (DAPs) to be created. The Disability Service should proactively identify and contract all students who have shared a declaration of disability/permanent condition. Students who engage with Disability Service teams benefit from discussions and Disability Action Plans being implemented before the start of the academic year, may better engage with their academic department, complete more time-intensive and administrative heavy tasks (e.g., applying for DSA and the Needs Assessment process), and can apply for additional support such as specialist accommodation, funding towards additional ensuite costs, car parking permits or non-DSA funded support. [Type 1 evidence]

- Self-reporting by students at the pre-entry stage or via an early assessment survey during the induction week at the HEP. This information can be used to better tailor staff training to individual needs and improve access to student wellbeing and self-help information (Baker et al., 2021). Once disability needs have been identified, the HEP should provide an individual appointment with a Disability Advisor at the pre-entry stage for the advisors to identify and share information with applicants regarding other transition interventions / programmes available at their institution. [Type 2 evidence]

Change mechanisms

- Improved support for disabled students that is provided early on → in-depth understanding of disabled students’ needs by HEP staff / peers → better provision and increased use of support, confidence among disabled students and impact on progression after HE

- Support by significant others (e.g., parents / supporters) → increased student confidence (and, therefore, sense of empowerment) in navigating HE → maximisation of student readiness and competencies

- Tailored staff awareness and training → increased staff confidence in supporting disabled students → improved student access to and use of support services

Assumptions

- 1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- 1.2 We assume that disabled students share information about their disability/ies as early as possible so that appropriate adjustments can be made to teaching, assessment, and pastoral care. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

- 1.3 We assume that the interventions/programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- 1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions/programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- 1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- 2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

- 2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

- 3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 5: Mentoring/buddying/tutoring

Intervention 5: Mentoring/buddying/tutoring

Disabled students may experience a range of academic and non-academic challenges that hinder a successful transition into HE. One way to address these challenges is through mentoring / buddying / tutoring schemes that can provide a mix of pastoral, social and academic support to students. While this activity could be delivered through three different formats (listed below), it is suggested that activities are underpinned by ‘person-centered planning’, which aims to prioritise students’ own goals, preferences, and priorities in service provision (ibid.). Specific training for mentors and ‘buddies’ should be organised by the Disability Service team to ensure mentors and buddies have the most appropriate skills to support mentees, are able to provide the most up-to-date information on disability support practices and facilitate the sharing of experiences.

Timing

Post-entry transition stages

Activities

Student-to-student (peer-to-peer) mentoring programme, in which mentors follow a curriculum structured by monthly and weekly goals. Evidence suggests that this format could be beneficial for mentees, especially in relation to learning how things work at the HEP, to meet people on campus, and to access support (Hillier et al., 2019) including on using assistive technology. The evidence indicates that for this intervention / programme to be successful, mentees should be recruited by disability support staff based on their judgement of the students’ needs for additional support, as well as their interest in participating. Mentors should be peers or senior students, willing to participate and be matched with mentees by availability. Having lived experience of disability is desirable but not essential. [Type 2 evidence]

- Campus ‘buddy’ programme. Like the peer mentoring activity, campus buddies should be assigned to disabled students in the instances where Disability Service pre-entry work shows that this could be helpful. For example, one aim for the ‘buddies’ could be to support disabled students by meeting with them on a regular basis and sharing personal experiences of the academic and student life at the HEP. [Type 1 evidence]

- Faculty mentorship programme where specially trained faculty mentors provide tailored support to disabled students during the transition period. Evidence suggests that this type of programme should offer disabled students the opportunity to be paired with a faculty member for the duration of their first year at HE (Markle, Wessel and Desmond, 2017). It is recommended that an introductory email is sent to initiate the relationship, but the nature of it should be determined by the participants, including the frequency and manner in which the pairs should meet. Finding a system that is beneficial for both is essential. Faculty members should provide advice on how students could successfully complete their coursework, introduce them to resources and other faculty members. [Type 2 evidence]

Change mechanisms

Improved support for disabled students that is provided early on → in-depth understanding of disabled students’ needs by HEP staff / peers → better provision and increased use of support, confidence among disabled students and impact on progression after HE.

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.3 We assume that the interventions/programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

2.7 We assume that parents and supporters are receptive to the idea of transition support and understand the benefits it can accrue for students as they enter HE. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 6: HEP ‘taster’ days

Intervention 6: HEP ‘taster’ days

Taster days provide disabled students with open days to experience HEP life / access materials prior to entering HE to help them successfully get through the transition process. These events should also include information on approaches to inclusive assessment, campus accessibility and adjustments that can be made to accommodation to cater to their needs. This is important to enable students to understand what they can expect as a disabled student early on, for example, before an application to study at an HEP has been made. Course and subject specific information should be included together with the opportunity to meet academic staff and find out about teaching and learning requirements. Taster days should also include relevant professional specific information to ensure students are fully aware of teaching, learning and assessment requirements, and also profession practice where relevant

It is also important to note that information about early engagement events should be shared with, and be open to, all students. This should allow HEPs to target both those students who have declared their disability as well as those who are self-declared only. Events should be as accessible as possible and include information on disability support available. Some applicants may not yet be aware of diagnosis, may not want to share or may have disabled family/supporters who want to accompany them. Some targeted outreach and support can also be offered to specific groups – such as by condition, or by broader grouping, e.g., neurodivergent students.

Timing

Pre-offer or offer-holder transition stages

Activities

- HEPs could consider inviting prospective students to sit in on lessons with currently enrolled students and become part of the class for the day. This would allow students to engage in the HE experience, have a tour, meet current students and an opportunity to find out more about the learning environment. [Type 1 evidence]

- HEPs could also provide early access to HE courses, educational coaching and campus membership to disabled students during their final two or three years of secondary education. While this may be more complex to plan, implement and oversee as it requires working across two education systems (secondary and higher education), type 3 evidence (Schillaci et al, 2021) has shown it to lead to improved post-transition outcomes for disabled students, including self-determination and academic performance. [Type 3 evidence]

Change mechanisms

Early engagement with HEPs → students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey → improved knowledge and / or increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services

Familiarisation with and early awareness of student life → students are better prepared for HE → improved experience of HE

Early access to HE experience → increased disabled student self-determination (and, therefore, sense of empowerment) → improved post-transition outcomes

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.3 We assume that the interventions/programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 7: Early induction

Intervention 7: Early induction

Ensuring students know what they can expect as a disabled student early on (that is, at the offer-holder stage or at the start of an HE programme) is key. Early induction activities enable HEPs to provide support for disabled students from the start of the student’s HE journey and increase positive engagement with the support available, helping to minimise the chance of dropping out of their course. Induction activities should include the development of suitable guidance documents outlining how the course is taught and assessed (including the competence standards that students should be able to meet), and what support services are available to students, including reasonable adjustments available as a matter of course. HEPs should ensure that such information is on their websites and is up-to-date, easy to find and accessible.

Timing

Offer-holder or post-entry transition stages.

Activities

- Reviewing relevant information from the student’s previous educational provider or workplace about the student’s support and accessibility needs (with the student’s consent). This should include consulting any adjustment planner or passport that the student developed in a previous setting and has chosen to share.

- Establishing an integrated referral process between the different HE support services. An integrated process facilitates a joined-up transition journey and ensures students can access the support they need throughout their application process and beyond. For instance, this could include sharing relevant information between the Recruitment and Admissions team, the Student Support and Safeguarding team and wider academic staff. [Type 1 evidence]

- Induction with individual course teams where students are introduced to academic staff during their induction week and provided with opportunities to meet other fellow students at specifically organised events. They can also be provided with key information on their course, as well as key dates and points of contact in case they have any queries or in the form of an induction week workshop.

- Induction and familiarisation programmes for students and their parents / supporters, who should be invited to attend information gathering sessions, hear from current students, and form networks with other parents / supporters, with the aim of enabling them to confidently navigate and support their child’s transition. [Type 1 evidence]

Change mechanisms

Early engagement with HEPs → students integrate the lived experience of their disability with the HE journey → improved knowledge and / or increased confidence and trusting relationships with staff and support services

- Familiarisation with and early awareness of student life → students are better prepared for HE → improved experience of HE

- Support by significant others (e.g., parents/supporters) → increased student confidence (and, therefore, sense of empowerment) in navigating HE → maximisation of student readiness and competencies

- Integrated, joined up support provision → awareness, access to and use of support throughout transition (and, therefore, a sense of empowerment) → increased skills and knowledge for success in HE

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.3 We assume that the interventions / programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.4 We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Intervention 8: Staff training

Intervention 8: Staff training

Staff training is fundamental to ensuring successful transition into HE. This group of activities explores options for proactively engaging with HE staff to increase their knowledge of their legal duties, good practice, disabled students’ needs, the support available and ultimately encourage and enable them to signpost students to in-house support. Staff should be encouraged to work towards creating an inclusive learning environment and inclusive practice for students.

It is recommended that staff activities include disability awareness training, as part of which HEPs provide guidance on universal design and adjustments that can support students to help build staff knowledge and experience in this area. It is also important to educate Student Union (SU) staff about the needs of disabled students, as well as promoting SU accessible activities to reduce the risk of social isolation experienced by disabled students. Any activities completed should be referenced against clear learning outcomes (such as, increased understanding of the different types of disabilities), so that staff understand what the HEP requires of them in creating enabling environments for students. [Type 1 evidence]

Timing

For staff in relation to pre-offer, offer-holder or post-entry student transition

Activities

Provide all staff with case studies on disabled students’ learning needs and outcomes, including information on any HEP tools available to support them.

- Provide all staff with guidance on compassionate communication and affirmative approaches that recognise the existing strengths of students, moving them away from so-called ‘deficit’ approaches.

- Distribute longitudinal observations of personal academic tutorials to staff during the first academic term to strengthen their understanding of disability-specific needs.

- Encourage staff to develop a data collection and monitoring system for their engagements with disabled students by drawing upon or building up, where possible, existing data sources.

All these activities should be underpinned by targeted training for student-facing staff to raise awareness of the challenges disabled students may face and support for academic tutors on existing inclusive practice standards.

Change Mechanisms

Tailored staff awareness and training → increased staff confidence in supporting disabled students → improved student access to and use of support services

Assumptions

1.1 We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

1.5 We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.2 We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.3 We assume that education providers identify appropriate interventions / adjustments aligned with specific disabled student needs. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

2.4 We assume that staff and other stakeholders (such as peers involved in interventions / programmes) form supportive and trustworthy relationships with disabled students in all engagements conducted. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Hillier et al. (2019).

2.5 We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

2.6 We assume that staff will engage with training workshops and resources, and that this training will lead to a change in behaviours or attitudes towards students. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

2.7 We assume that parents and supporters are receptive to the idea of transition support and understand the benefits it can accrue for students as they enter HE. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

3.3 We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

Additional assumptions underpinning staff and other stakeholder related activity include:

- Professional, statutory and regulatory bodies (PSRBs) support staff clarity about reasonable adjustments or anticipatory inclusive design.

- Professional, statutory and regulatory bodies (PSRBs) provide clear information on fitness to practice in a way that supports disabled applicant knowledge of the benefits of a professional course of study.

- Staff have appropriate approaches to sharing information about disability with key colleagues and these do not put undue burden on students.

- Schools, uniconnect partners and other involved in outreach provide their activities in ways that are accessible or are supportive to the approach laid out here.

Intervention text

Needs assessment

Planning for the transition process begins as early as possible is important to the success of transitions support. It is also important that both pre- and post-entry needs assessments are conducted to identify key transition requirements so that they can be addressed with reasonable adjustments and other tailored activities / programmes.

To clarify, needs assessments can be wider than an assessment specifically conducted for receiving a Disabled Students’ Allowance (which all HEPs may not be validated to conduct). To do this, it is advisable that key stakeholders are involved in the process, including disabled students themselves (for example, by declaring their disability), parents/supporters (for example., by supporting the transition), and HEP administrative and academic staff (for example, the Disability Service team).

Timing: pre-offer, offer-holder, or post-entry transition stages

Activities might include:

- Parent / supporter-educator consultations at local schools to provide parents and supporters with information about the support available at HE as well as the life skills students need to develop during their first term. Type 3 research has shown that parents and supporters of disabled students prefer to be more involved in the transition planning process (Ruble, McGrew, Toland, Dalrymple, Adams and Snell-Rood, 2018). Parents and supporters are lifelong advocates for many students with disabilities and sharing that information with them can help maximise students’ readiness and competencies across the different life skills that are required when entering HE. [Type 3 evidence]

- Direct referrals to the Disability Service team for tailored Disability Action Plans (DAPs) to be created. The Disability Service should proactively identify and contract all students who have shared a declaration of disability/permanent condition. Students who engage with Disability Service teams benefit from discussions and Disability Action Plans being implemented before the start of the academic year, may better engage with their academic department, complete more time-intensive and administrative heavy tasks (e.g., applying for DSA and the Needs Assessment process), and can apply for additional support such as specialist accommodation, funding towards additional ensuite costs, car parking permits or non-DSA funded support. [Type 1 evidence]

- Self-reporting by students at the pre-entry stage or via an early assessment survey during the induction week at the HEP. This information can be used to better tailor staff training to individual needs and improve access to student wellbeing and self-help information (Baker et al., 2021). Once disability needs have been identified, the HEP should provide an individual appointment with a Disability Advisor at the pre-entry stage for the advisors to identify and share information with applicants regarding other transition interventions / programmes available at their institution. [Type 2 evidence]

Change mechanisms

Improved support for disabled students that is provided early on → in-depth understanding of disabled students’ needs by HEP staff / peers → better provision and increased use of support, confidence among disabled students and impact on progression after HE

- Support by significant others (for example, parents/supporters) → increased student confidence (and, therefore, sense of empowerment) in navigating HE → maximisation of student readiness and competencies

- Tailored staff awareness and training → increased staff confidence in supporting disabled students → improved student access to and use of support services

Assumptions

- We assume that students have time available and invest it to actively engage with HEPs and to take up the support on offer to them during their transition journey. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- We assume that disabled students share information their disability/ies as early as possible so that appropriate adjustments can be made to teaching, assessment, and pastoral care. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

- We assume that the interventions / programmes generate awareness and confidence among those that have not shared information about their disability to declare or seek targeted support. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- We assume that disabled students welcome the opportunity to learn about disability support from HEPs and related interventions / programmes and engage with them. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel and Desmond (2017) as well as Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- We assume that disabled students experience their engagement with staff and other stakeholders as being supportive and trustworthy. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

- We assume that education providers are proactive with supporting students with a disability and reflect their commitment through activities such as staff training, student access to disability services / resources. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Baker et al. (2021).

- We assume that faculty members understand the importance of their role in the academic success of students with disabilities and the reasons why transition into HE might be more difficult for students with disability. This is based on Type 2 evidence from Markle, Wessel, and Desmond (2017).

- We assume that there are sufficient resources available for implementing a programme of transition support at HEPs. This is based on Type 1 evidence from HEPs delivering transition support for disabled students.

-

Guidance and resources

-

Guidance and resources

-

Report

-

Project

-

Report

-

Report

Report | What works to reduce equality gaps for disabled students

16 February 2023 -

Project

Project | What works to reduce equality gaps for disabled students

17 February 2022